By Dr. Ebuka Onyekwelu

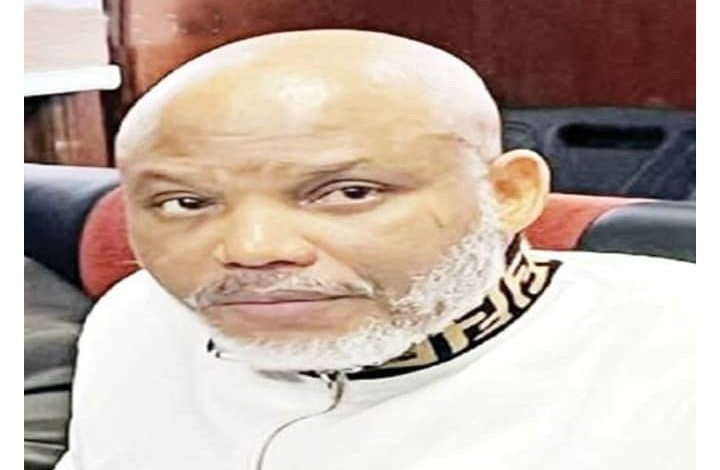

Yesterday, Mazi Nnamdi Kanu was sentenced to life imprisonment with an additional 25 years over sundry charges relating to terrorism. Kanu was summarily linked to the violence that erupted following the October 2020 EndSARS protest, which led to the destruction of police stations and mass stealing of arms and ammunition across the Southeast. In several broadcasts on Radio Biafra, Kanu called on his followers to “cut down” security operatives and “seize their arms” around the time of the EndSARS protest. By December of the year 2020, Kanu announced the formation of Eastern Security Network, ESN, as the military wing of IPOB, charged with the responsibility of protecting the Southeast and Southeast forests from “Fulani invaders.” Kanu further issued several orders to his followers to kill those he deemed to be opposed to his ideas and means to a free and sovereign state of Biafra. A few months after the creation of ESN, in the first quarter of 2021, the Southeast was rapidly enveloped by insecurity. The insecurity was novel to the extent that things began to fall apart with such intensity that it made people honestly wonder if it was internal or an invasion. From 2021 to date, the Southeast has never been its former self. Though the sign of violent agitation was always palpable, it was somehow overlooked.

Nnamdi Kanu had anchored his agitation on the protection of the lives and properties of Southeasterners from Fulani invaders, whom he said had hatched a grand plan to invade the Southeast. So fundamental to Knau’s agitation was herdsmen violence against farmers in the Southeast that the ESN was solely created to push back the herdsmen. For context, by 2020, herdsmen had attacked several villages in the Southeast over disputes relating to herdsmen trespassing into cultivated farmlands with their cattle and causing significant economic damage to farmers. Typically, trespass into cultivated farmland elicited resistance from farmers and often prompted the herders to retrieve and retaliate with gun violence. This pattern of conflict remains consistent and almost the same in all cases of dispute between herders and farmers across the Southeast. From 2016 to 2025, the Southeast has recorded multiple tens of reported cases of herdsmen violence across all five states of the zone, with most recording at least one death. Herdsmen violence or crisis with farmers is an ongoing dispute that has gained global prominence, with a significant amount of violence in the West African sub-region linked to the farmer-herder crisis. The problem is also blamed on global warming, which has led to a remarkable decline in Lake Chad, thereby further deepening the chances of clashes between farmers and herders in Nigeria and other countries benefiting from Lake Chad. Constrained by these weather changes, herders move about in search of forage for their animals, which makes clashes with farmers almost inevitable. However, it is difficult to explain the rationale behind grazing in cultivated farmlands.

In the case of the Southeast, given the rising attacks by herdsmen across the zone, be it in Uzo-uwani, or Aha-Amufu, or Isi Uzo, all in Enugu State, or in Uturu, or Isiukwuato, or Uzuitem, all in Abia State, or the attack in Ogbaru, or Anyamelum, or Ebenebe, or Anambra West, all in Anambra State, or the one in Ishielu, or Izzi, or Mbom, in Ebonyi State, or the one in Amakohia, or Oguta, in Imo State, the Southeast populace were faced with a real fear, resulting in a deep disliking for herdsmen much so that their sight created apprehension. The attacks further gave impetus and some form of credibility to Kanu’s claims that there is an intent to invade the Southeast by Fulanis for religious reasons. Apparently sensing the passion invested by Southeasterners in this farmer-herder dispute, Kanu then went on to feast on the people’s fear and vulnerability in the absence of the government’s assurance over the safety of the people of Southeast. Mazi Nnamdi Kanu quickly filled the leadership void, and many people ignorantly followed his offensive and abhorrent orders. To add to it, he eliminated chances of any interrogation of his ideas and method by labeling people “sabo” or “ottellectual,” thereby forcing dissenters of Southeast extraction into long silence with the threat of violence.

Nnamdi Kanu’s case must therefore serve as a lesson for Nigeria in how not to govern a country. Just as Kanu’s sentence has done justice to the victims of senseless carnage by armed bandits and criminals in the Southeast masquerading as freedom fighters under diverse guises since 2021, the government must also ensure that justice is done for the victims of herdsmen violence in the Southeast and beyond. The Nigerian government must prioritize the well-being of its citizens and be swift in addressing violence, rather than planning with a huge budget and undertaking extensive work later. Efforts must be made to solve problems at their earliest stage as they arise.