By Tony Okafor

In the quiet belly of Umuagu, where the red earth clung lovingly to bare feet and palm fronds hummed secrets to the harmattan breeze, there lived a boy named Ihekwoaba — the lone star in his parents’ sky, the only surviving son of Nganwuchu and Ekeiaku.

He had three sisters — Wawa, Agnes, and Ogbealu — but it was Ihekwoaba who bore the family’s future on his fragile back.

His mother called him Ihekwoaba, nwa m ji eme onu — “my pride, my song.” His father would rise before the cocks and pour libations at the shrine, whispering prayers into the clay:

“Let this one live. Let this one outlive me.”

Their desperation was not unfounded. Before Ihekwoaba, three male children had been born — and three had returned to the earth too soon. Fever had taken one. Convulsions claimed another. The third simply stopped breathing one cold night and never woke.

So when influenza stormed the village again and wrapped its claws around young Ihekwoaba, the family braced for another burial.

But fate — or perhaps the gods — had different plans. Ekeiaku gathered roots and leaves from the ohiaogba forest, brewed concoctions with trembling hands, and forced the bitter brew down her son’s throat as he burned with fever.

And he lived.

From that day, Ihekwoaba was no longer just a child — he was a living miracle. His father built him a stool of iroko wood and vowed,

“No teacher shall raise a cane against this one! Let him learn from the soil, not the school.”

So, while other boys recited alphabets and scratched slates, Ihekwoaba walked barefoot behind old farmers, learning the language of yams and rain.

He listened as they told tales of the yam spirit, Ifejioku, and how a man’s strength was measured by the fullness of his barn.

He watched the wind carry dust across the fields and knew when rain would fall before the clouds gathered.

And the land, pleased with the boy, opened its breast to him.

By his thirties, Ihekwoaba’s farm stretched like a kingdom — hills rolling in his name, cassava singing in rows, yams fat as drums. He owned goats that danced like masquerades, and chickens that pecked with pride.

When he walked through the village square, even titled men paused to greet him.

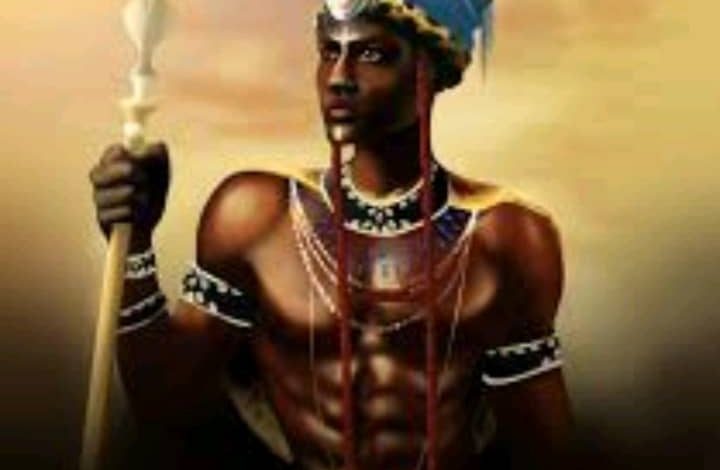

In time, they gave him the cap of Nze — a sacred crown bestowed only on the wise, the generous, and the fearless.

At village meetings, when Ihekwoaba rose to speak, even children fell silent. His words did not fall like leaves — they landed like stones in a still pond, rippling outward.

But not all hearts beat for his success.

In the corners of family compounds, cousins whispered. Some clenched their jaws and fists in silence.

To them, his rising sun only deepened their shadows. Envy ripened like bad fruit. First, they laced his palm wine. He spat it out before the bitterness touched his throat. Then, they buried charms beneath his farm path — but his yams still flourished. At last, during a community feast, they poisoned his meal.

That night, Ihekwoaba screamed into the void — his body contorting, his mouth foaming, his voice choking with pain. The villagers gathered, weeping, certain death had come for their lion.

But Ihekwoaba did not die.

He battled death like a wrestler in the dust and returned gasping, victorious. The next morning, he sat beneath the udala tree, pale but smiling. The elders called it a wonder. The villagers whispered,

“His chi is not made of clay… it is forged from iron.”

And so, his legend grew.

He married many wives whose joy echoed through his compound like music. His children were strong, especially the sons — six in number, each carrying his fire in different forms. His barns grew fat with yam. His walls were painted with pride.

In his old age, Ihekwoaba’s back bent like the bow of a hunter, but his voice still cracked the silence like thunder.

He would sit under the same udala tree, snuff container in hand, watching his grandchildren chase lizards across the compound, a soft smile playing on his lips.

The boy once too precious to be caned had become a man whose shadow stretched across time.

And long after his bones had returned to the red dust of Umuagu, the villagers still told the tale:

“You want to understand how a man survives envy, poison, and plots — and still rises?

Ask for the story of Ihekwoaba.

The gods did not just spare him… they crowned him.”